| Effects of Different Lighting Angles | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

In 1932, a Yale University professor named Stanley McCandless published a book called A Method of Lighting the Stage. In this and in his previous book, A Syllabus of Stage Lighting, Dr. McCandless detailed many of the concepts and techniques we still use today, including the breaking down of the stage into individual areas, the functions and qualities of light, and — most important, for this section — the angle from which we light the performers.

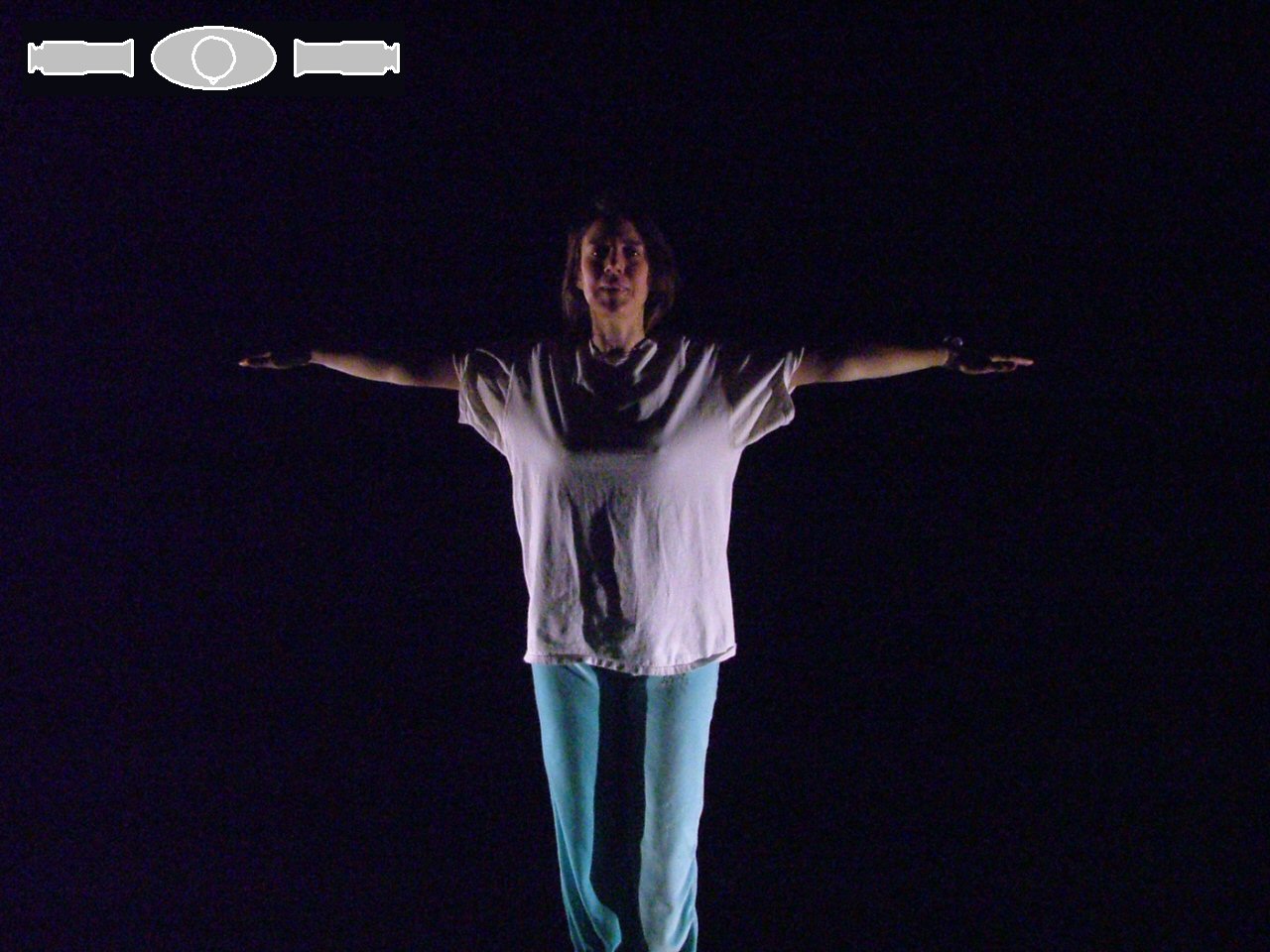

Look at photos #1 and #2, below. In each case, the actor is lit by a light coming at a vertical angle of 45� and from straight DS of her. You can see that, while her face is, indeed, lit, the effect is somewhat stark. Dr. McCandless posited that the most flattering way to light the human face is from 45� up and 45� to the side, as in photo #3. The problem with this is that, one side of her face is relatively dark; the audience seated to SR of her will see mostly shadow. Dr. McCandless's solution was to bring in a second light, a mirror image of the first, from the other side. As you can see from photo #4, the actor is now lit from both sides, but looks two-dimensional. Dr. McCandless's solution to this was to make on of the lights "warm" and the other "cool", as in photo #5. Note that the contrast between the two colors need not be as great as in this example; "warm and "cool" are relative terms. This approach is known as the "McCandless method", or "McCandless angles", and is still widely used. Of course, the needs of every show are different (There is, after all, a reason that Dr. McCandless entitled his book, A Method of Lighting the Stage instead of The Method of Lighting the Stage), but more often than not, McCandless angles (or some variation thereof) will serve you well for lighting actors' faces. ...However, lighting faces is not all we do. Look at photo #5 again. Note that her face has a nice, 3-dimensional quality but her body is less so, and her dark hair completely fades into the black backdrop. We solve this by using side and back light. Look at the actor in photo #6. You can see how her body is "sculpted" by the sidelight. The folds in her tee shirt are in high relief, and she seems to "pop" out from the backdrop (aided, of course, by the white fabric and the lighter-colored hair). These sidelights are from a fairly high angle. In photos #7 and #8, you can see what happens when we put our sidelights on the floor (These are called, "shinbusters," for reasons which must be obvious). Since light from below is rarely found in nature (sunset, sunrise, and light reflecting off the ground are notable exceptions), shinbusters give an eerie, other-worldly effect. They also tend, visually, to elevate the performer off the floor. Sidelight, whether shinbusters or "high sides" is helpful for sculpting the body, but, as you see, does not light the face well. Now look at photo #9, which shows the actor lit only by a light from US. Backlight, even more than sidelight, makes the actor's hair and body "pop" out from the background, but it's even worse than sidelight in lighting the face; in most cases, a play, or even just a scene, lit only with backlight would be unwatchable. We will usually want a mixture of all three, with the exact proportions determined by the needs of the individual show and, often, the individual scene within the show. Howard Bay referred to this use of multiple angles as "jewel" lighting, a reference to the way jewelry is lit in a display case. The above, of course, is based on the premise that we're working in a proscenium theater; in non-proscenium seating arrangements, such as arena or thrust staging, one audience member's frontlight becomes another's backlight. In these cases, the designer needs to arrive at a happy medium and accept that not every audience member will see the show exactly the same way. |

||||||||||||||||||||

Many thanks to actors Wendy Mapes and Erika Iverson of Magis Theatre Company (New York City) |

Sales Manager Lok

Sales Manager Lok